I’ve noticed that there seems to be a big proportion of contortionists who also have co-morbid mental health conditions such as Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC) and ADHD/ADD. Other mental health conditions- such as anxiety, eating disorders, a history of trauma- also seem to be more common. In general, neurodivergence seems to be over-represented in contortion populations. But what accounts for this?

In my opinion, this is partially because there is an established link between hypermobility disorders such as Joint Hypermobility Disorder and Ehler-Dahlos’s Syndrome and autism. Some studies suggest that around 50% of autistic people have EDS/JHS, as opposed to 20% of the general population (click here for a useful powerpoint slide on this topic). So, proportionately speaking, the people who are attracted towards contortion would more likely to be on the spectrum. However, I do want to explore how contortion training has a positive effect on autistic people not just in terms of improving motor coordination, but also in terms of grounding, increasing interoception (ability to recognize your internal processes) and even encouraging socializing.

For interest of this blog, I will be talking mostly about my experiences as an autistic female. However, you may find a lot of my accounts will pertain perhaps to other similar neurodivergences, as well.

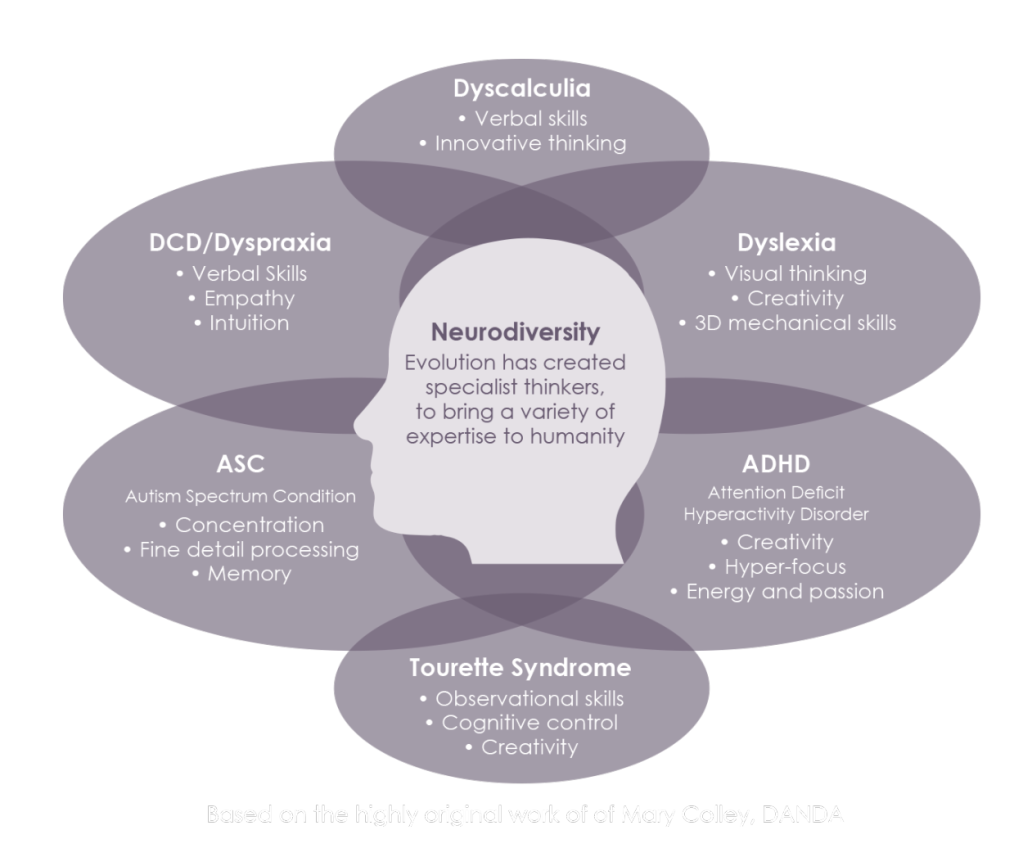

What is Neurodiversity?

Firstly, let’s define what neurodivergence is for those who aren’t familiar. The neurodiversity paradigm is a concept popularized by Steve Silberman who wrote Neurotribes (a very interesting read I encourage everyone to look up) that conditions such as autism and ADHD are the product of having a different brain wiring than ‘normal’: meaning not only is our thinking different, but the way we sense and process physical, sensory, social and internal sensations are different as well. This can even apply to the way we are affected by medication.

This paradigm basically encourages the viewpoint that these conditions aren’t diseases that need to be cured, but understood so as to provide different supports. Disability is a product of having to live in society, rather than something that is a problem-into-itself. The analogy I like the most is if you imagined you were an alien who descended on planet earth without an instruction manual: you may feel, sense or interpret information differently and you may need to learn social skills from the ground up.

Contortion and Regulating the Nervous System

To be honest, you can’t “control” your nervous system: you can only control how you respond to stimuli as it happens. Your nervous system does whatever it wants, and you choose how to respond to it. However, generally having a regulated nervous system also contributes to better functioning, less hypervigilance in the face of triggering stimuli, as well as better awareness and understanding of internal body sensations.

As an autistic person, high levels of anxiety is really common. When I say this, I don’t exactly mean anxiety as a disorder. I get anxious because of (what I think) are very rational reasons: slight changes in routine, unexpected stimuli, unpredictability of social situations, etc. So, I would say that for an autistic person that anxiety is a rational response to life, which is why we get so anxious so easily. Our nervous systems are just highly attuned to stimuli, and so we get affected by things that normal people may be able to brush aside easier. I like to distinguish autistic anxiety from regular anxiety in this way: A person with an anxiety disorder may spend more time imagining scenarios that cause them anxiety. Autistic anxiety is more about hypersensitivity to a difficult environment.

This also applies to eating, drinking (interoception: awareness of internal body sensations like hunger and thirst) and general awareness of pain. Most autistic people either have hypo/hyper-sensitivity to pain and sensory input. For me, it’s very hard to know when I’m hungry or thirsty until it’s overwhelming. I can easily ignore the feeling of a burning stove in order to get something out of the oven, as it seems to be less effort than thinking of the steps needed to not get burned. However, the sensation of salt underneath my feet can send me into a meltdown because it registers as unbearable pain. So, autism is often characterized by under and over sensitivity in general, and it can seem like the world is very chaotic and hence, order is needed in the form of routines and rules.

How does contortion help this? A lot of contortion poses are internally distressing. Lunges, chest stands, teardrop, needles: all these types of shapes tend to trigger flight-or-flight feelings when entering. However, just the act of forced mindfulness- forcing oneself to calm down in the midst of overwhelming internal stimuli, creates an almost weird conditioned response in which I react to perceived “pain” or fear with calmness. When I enter into a chest stand, my mind almost subconsciously calms down, as I’ve “brainwashed” myself into accepting this range as normal. Over time, it does become normal. Contortion becomes a way for me to be completely attuned to the present, to meditate and focus on internal sensations and to calmly accept and process them. If I feel intensity, I breathe. If I feel heaviness, I enter into it. This is what I call the ‘drama’ of contortion: the feeling of overwhelming internal sensation. And to overcome it, we exercise equally excessive mindfulness.

This ability to center and “meditate” in contortion poses doesn’t always translate to everyday life. I still get upset at slight changes. However, I feel like I am better equipped to deal with them: the ‘drama’ of contortion outweighs the drama of everyday life. So, even if I am overreacting to a stimulus that shouldn’t be worthy of over-reaction, the effect is significantly blunted. Instead of melting down over a change of meal plans, I am better able to just accept change as it comes. This is generally better, of course, when I’m in an overall better mental state. If I’m burned out, the positive effects of contortion get erased as my brain has less energy to handle things in general. So, just being aware of what gives and takes energy from me is something I need to be continuously conscious of, which I will get to later.

I would also add that these positive effects I’ve mentioned that contortion provides affect everyone at large, whether neurodivergent or not. In fact, it benefits particularly people with an internal disconnection with their bodies, as in the case of trauma and eating disorders, all of which are often co-morbid with neurodivergence. As such, they soften the blow of having to exist in a society that may not be built for us by giving us more tools to cope and adjust our mental energies.

Special Interests, Sensory Processing And Socializing

There is also the issue of special interests, which is the term we use for an autistic person’s “restricted and limited interests” according to the DSM-5. When phased like that, it sounds quite negative. However, I think it’s one of the main joys of being autistic, as it provides passion and purpose that I never have to look for.

It has been said (read: “Rethinking Repetitive Behaviors in Autism“) that the areas of the autistic brain that are usually wired for social interaction are wired for special interests. In other words, the energy that people would usually spend on deciphering social cues, seeking external validation and relationships are usually channelled to our interests and passions. As you can imagine, this means that we can get good at something very quickly.

Personally, I think that part of the reason why I got good at contortion so fast isn’t so much a matter of talent, practice or even good coaching, but because of the obsessive zeal that a special interest provides. Part of the reason why I started this blog is so that the Amy in the early days of her contortion obsession would have appreciated stumbling on such a resource, since I spent so much of my time reading every possible resource I could find (there isn’t/ wasn’t many). If you spend every waking hour considering a topic, you get good at it purely by the amount of energy you’ve put into it. So, the obsession that my special interest provides me as well as the ability to hyperfocus on a topic is a huge factor in how I improved so quickly.

Another interesting aspect is how contortion affects my perception of sensory stimuli. I’ve found that I am able to focus on my training within my own internal “contortion bubble” even in the face of loud, distracting sounds/ noises/ movement. In a way, it feels like having an invincibility that only occurs when I train. It doesn’t exist outside of it: if I’m walking down a busy street or walking into a busy restaurant, I still get overwhelmed to the point of nausea and/or disassociating from the situation. However, this ‘immunity’ I feel when I do contortion seems like a superpower for someone who is generally oversensitive to such things.

Again, this decreases with added stressors. If I have a performance to prep for or a lot of social / work pressure, I am more in a position to meltdown because of such stimulation, but it has only happened maybe twice so far in three years, which is nothing compared to how often it happens in regular life. Both times involved the pressure from having to prepare a rather intimidating performance.

As for socializing, I seem to be able to relate better to other people when it concerns my special interest. There are studies that show (Read: “The Benefits of Special Interests“) that autistic people can initiate and engage better in conversation, make eye contact and even fidget less when involved in their special interest. I have definitely found that something such as eye contact, which I usually find unbearable, is doable when being coached or talking to friends about contortion. Of course, there is the risk of info-dumping in a conversation, but circus humans are generally more accepting of such proclivities, as circus seems to attract neurodivergent people, anyway.

That being said, I spent a lot of my early contortion days totally isolated, practicing and occasionally being coached. When being coached, I rarely interacted in a social way with my coaches, obediently following their instructions (making me a rather good student), even if I didn’t understand it completely at the time. This improved over time, however. The more I practiced contortion, the more I was able to socially interact even if in a very limited way. I still prefer the company of one or two as opposed to multiple people and I prefer online relationships to in-person ones, but this is also a matter of personality.

Contortion And Learning Disabilities

I have found that I have more difficulties with proprioception and understanding verbal cues than the average person. If someone goes off into anatomical jargon, I completely lose them even if I understand those terms normally.

Take note, being coached means I have to take in physical stimuli, internal sensations, verbal cues and social contact all at once. It’s a lot to handle in the space of a small window of time. If someone insists on talking in “anatomical poetry”, I think this is a very ableist way of coaching as they are valuing how smart they sound over their student’s ability to translate those cues into their body. For someone with pretty bad internal awareness, I have already have enough to deal with without having to translate what I think someone is saying into normal human words, then translating that into my body.

For those who coach neurodivergent people: please simplify your language, use imagery or videos to illustrate your concepts, and be creative around how you may want to explain something rather than repeating the same cue expecting a different result. Sometimes, I hear something like “bring your hand to your shoulder”, and I can’t understand it: which direction, how? Does my elbow wing out or stay in? Which shoulder do I tap? Even a simple change of phrasing like “swat a fly on your opposite shoulder” helps me to understand better because it reduces the options for wrongful interpretation. If we don’t understand something simple, it’s often because of an auditory processing issue. Be patient, change your words, find a different angle to relate to us with.

When I coach, I also try to use imagery to get my point across. For example, to cue the hip lift in cobra, I do explain the anatomy separately using a doll sometimes if that’s something my students enjoy. But when I actually cue it live, I just say “lift up and over like a rainbow”, so it’s easy to visualize. Sometimes, it does help to explain technically separately, but to only use simple cues when actually coaching so the brain doesn’t have to grapple with multiple stimulus, in addition to interpreting what you’re saying.

If you are excluding someone based on their lack of knowledge of anatomy, you’re being privileged and exclusionist. Please try to always translate things into laymen’s terms. Most coaches don’t have such anatomical knowledge: don’t take it for granted anyone can understand what you’re saying. It’s hard for the ordinary neurotypical person, and even worse with someone with auditory processing issues.

Also, take note that people with hypermobility and neurodivergence all have poor proprioception, in general. I’m inordinately clumsy in my daily life, but amazingly coordinated when I train. Why is it that I feel more comfortable upside down than right-side-up? I think it’s partly due to focus: contortion and hand-balancing forces me to be completely tuned into the present moment so I know exactly where my body parts are in space. In my daily life, I am constantly banging into things and getting unexplained bruises. Contortion hasn’t exactly improved my everyday coordination, but it has made me conscious that I *can* control it if I expend the effort to.

If you’re someone coaching someone with proprioception issues in general, see if you can explain things in a way that doesn’t include directional cues or body parts per se, as those cues are very confusing. If you explain things in a more figurative way or find other modes to explain a concept (through videos, visually or through metaphors), it will help your student to understand better what you’re trying to accomplish.

Contortion Coaching And Neurodivergence

Ironically, because I am slower at understanding what people are saying, it gives me a deeper understanding of contortion to be able to coach it. I’ve obsessively thought about every single element of every single shape. Teardrop? I’ve thought about all the different variations that can occur depending on each person’s body proportions, their natural strengths and weaknesses, their natural flexibility, their balance, etc. I’ve thought of every way to change it in every permutation: bringing it into a headsit, deepening it into a backfold, entering into it in 10 ways. Take this, and apply it to almost everything from the humble lunge to the impressive contortion push up.

Apart from constantly dissecting all the technical elements of a move, I also have a natural eye for detail, sometimes to a fault. I notice small, slight deviations in whether you’re twisting in a lunge, and whether that comes from your hip, lower back or shoulder. This ability to see detail is very useful for coaching, as I am able to detect cheats easily, without much effort. And having an exhaustive vocabulary to draw from helps me to troubleshoot what may fix it.

My knowledge of contortion is not static. Rather, it’s a nebulous creature that adapts and changes depending on new input. So every student I’ve taught and will teach will shape my current understanding of something. I learn the most from my students than from myself or my coaches. Having access to a wide variety of body types, backgrounds and abilities makes me privy to the spectrum of diversity that comes with training contortion, and how contortion training needs to be adapted to each person’s needs, rather than dumping the same cue on everyone and hoping for the same effect.

Contortion As An Identity: Being an “Alien”

I’ve found that contortion, in general, attracts people who identify as ‘alien’ or other. As neurodivergent people sense, feel and think differently from the norm, there is less in mainstream culture that we can relate to. The look of horror, disgust, confusion that contortion elicits often feels like a positive way to channel feelings people usually have towards me outside of contortion.

People sense difference. And sadly, they usually can’t handle it. Most people can only project their own experiences on other people and they fail to show empathy for someone who has a different way of relating to the world. Ironic, because autistic people are supposed to have diminished empathy (to an extent, this can be true, but it’s a bit more complex than that, never mind the fact I think all displays of empathy are just an act). A lot of us feel the effects of other people’s emotions and are continuously trying to relate to ‘normal’ people so as to fit into society. We just don’t express it in a typical way. Knowing you’re innately different, that people will notice it and sometimes discriminate you for unknown reasons is scary.

When someone shows alarm and concern about my identity as a contortionist or when I perform contortion, it actually filters all those unpleasant feelings of being judged for unknown reasons into a palatable form. Finally, there is an identity I can relate to that’s not human, because I have a lot of difficulties relating to the human race.

Tips on Training With Disabilities

Take note that a lot of the issues that affect neurodivergent people also affect hypermobile individuals when it comes to contortion training: impaired proprioception, dysautonomia (dizziness upon standing), brain fog, anxiety, memory issues, as well as sensory issues and fatigue. All these issues make contortion training complicated, especially if you’re having a low energy day. Know you just have more on your plate, so it’s okay if you don’t kill your goals every training day.

Personally, I’ve noticed that contortion training, most of the time, gives me an energy deposit. However, this doesn’t really help in the presence of other stressors. I’ve been doing this practice called “energy accounting” (which you can read about here) in which you write down a list of activities that give and take energy in your day and you add it up at the end. If you have a deficit of energy, it could explain why you can’t cope with simple situations such as answering your emails or taking a bath. Energy Accounting makes me more conscious of what activities give and take energy, giving me more control over my mental health and functioning levels. When I stay on top of it (even if it means just taking notes throughout the day if I’ve the energy), I have noticed I don’t meltdown or shutdown as often. So, it works.

Another thing is to consider is making sure you choose a coach that you can relate to and understand properly. If your coach is not making an effort to understand your special needs but demeaning you (this applies to everyone, not just neurodivergent people), they aren’t a good coach. I don’t care if they’re an amazing performer: it’s all null. Remember neurodivergence and hypermobility both come with proprioceptive difficulties that is often accompanied by slower processing of physical cues. Make sure you find someone who is creative enough to adapt to you, but also patient if you’re having a slow processing day.

Lastly, be patient with yourself and your own needs. If you’re hypermobile and neurodivergent, chances are your base level of energy is lower than average. The simple things- proper nutrition, hydration and sleep- matter much more than you think, especially as an athlete. These are things you can control. Treat them as non-negotiables: you don’t have an option to neglect them if you want to train properly. They should be your priority, even before training. A healthy body means a healthy mind, and vice versa.

In Summary…

I have noticed that contortion, in general, helps everyone in different ways. It is, ironically for what it looks, a ‘healthy’ activity for the mind and body. For purposes of conciseness (of which I am definitely failing), I am limiting the scope of this blog to neurodivergence. However, many of the points I’ve mentioned apply to anyone dealing with any mental health issue, and even when you don’t have any. So, please don’t think I’m saying that you can’t train contortion if you’re not neurodivergent. The world has already been made for neurotypicals, so I thought it would be nice to discuss how neurodiverse people relate to the world and how contortion training can help it as a form of therapy, or even as a passion and special interest.

Lastly, the connection between hypermobility and neurodiversity is an interesting topic I have only briefly covered. A lot of the little understood mental and physical issues that come with hypermobility also affect neurodiverse people, so there is a significant overlap between both populations. I would hope that all healthcare providers and coaches who work with both populations consider neurodiversity as a factor for the physical problems hypermobility may bring, and vice-versa. I think having knowledge of both topics grants you extra tools to be able to cope better in an overwhelming world.

If you’re hypermobile and neurodivergent, or if you’re hypermobile and not, I hope you find this article of value. I would love to hear about your experiences of how contortion helped you in any of the aspects I’ve mentioned or if you’ve any insights you’d like to share to further our understanding of how these topics relate. Happy training!

Some Links That Might Be Of Interest For Further Reading

Rethinking Repetitive Behaviors in Autism

The Benefits of Special Interests in Autism

NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity

Hypermobility and Neurodiversity: Dr. Jessica Eccles Lecture

Anxiety and Hypermobility – Dr. Jessica Eccles