A lot of people think of upper back extension as mystical because the upper back isn’t made for bending backwards but for twisting. However, doing unnatural things is part and parcel of contortion, we just have to be strategic about *how* we use muscle engagement to achieve the impossible. In reality, upper back engagement is simple and involves two vital things: proper shoulder and neck engagement.

There are a couple of concepts that are key. Firstly, your upper back and your shoulder blades are separate units and can work together or against each other. This means you can have a super flexible upper back and bad shoulder flexion and a very stiff upper back and good active shoulder flexion: the two are not mutually exclusive. Being able to use the proper shoulder engagement in the appropriate context is key to opening up through the back line of muscles in your upper back. Secondly, your neck (the SCM and deep neck stabilizers) help your sternum to pull through, opening the front of your upper back (your chest). If you can understand how to use the muscles around your shoulder blades (your shoulder girdle consisting of your lats, rhomboids, serratus anterior and upper + lower traps) with your superficial and deep neck muscles, you will be able to open your upper back.

Your Upper Back and Shoulder Blades Can Be Friends or Enemies

Your spine is not connected to your shoulder blades, which I know does not sound intuitive. Oftentimes, people will reach blindly back when their shoulders are overhead without the proper engagement, making their lats shrink and thus dumping the bend lower down into their lower or mid back. Likewise, the tendency when the shoulders are closed is to over-squeeze the rotator cuffs and not use the muscles between your shoulder blades to open your chest. In this part of the blog, I will discuss how to use your shoulders when they are closed (not overhead) and secondly when you’re in a shoulder flexion (reaching for something).

When Shoulders Are Closed (shoulder extension in physio terms), “Close The Gate”

When your arms are by your side and the shoulders are closed, shoulder engagement can be thought of as “dramatic yawn”. You are trying to squeeze your shoulder blades towards each other to open up through your chest. Oftentimes, people will roll their shoulders back and over-tense their pecs and the front of their shoulders to get their shoulder blades to squeeze together. Try to think of shoulder blade squishing inwards as a gate closing to allow your chest to open, rather than a motion of the arms pulling backwards. When you are able to feel the yawn properly, it will often feel as if your sternum/ chest is about to burst. If you have tight pecs, you will often hear a sternum crack, hence I sometimes cue this movement as “yawn until you feel an alien is about to burst out of your chest”. Take note that you can yawn with your arms straight by your side (as in cobra), with your elbows bent when your hands are on a chair or with your elbows out by your side (as in the picture). This engagement applies to positions such as cobra, in particular, where you are retracting the shoulder blades towards each other to open the chest.

Take note that this engagement does *not* apply to contortion hand balance. When the shoulders are closed and you’re in a handstand, you still need to shrug and wrap your shoulder blades, which I will explain in the next section. As such, what I’ve written above is more of a guideline with multiple exceptions, so you can simplify how you think about shoulder blade engagement.

When Shoulders Are Open (shoulder flexion in physio terms), “Open The Gate”: Shrug And Wrap

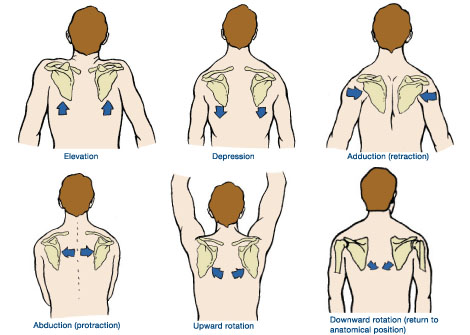

When your shoulders are overhead (what we call extension in contortion, but flexion in physio terms; for purposes of clarity, I’ll be referring to this as shoulder flexion), there are three main things that need to be done: elevation, protraction and external rotation; the former I call “shrugging” and the latter two I call “wrapping”. But what exactly does this mean?

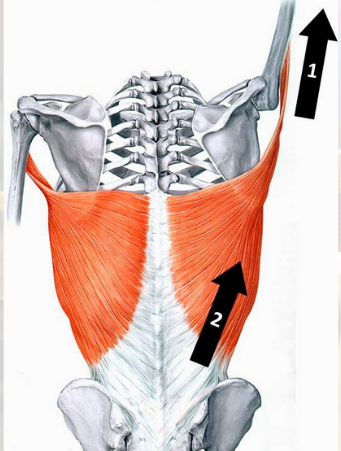

Elevation is often mistaken with upper trapezius engagement. People will shrink their necks and over-squeeze their upper traps to bring their shoulders to their ears, but this only engages the upper part of your shoulder girdle and puts the rest of your shoulder girdle on slack. In reality, elevation needs to come from your entire lats extending to pull the shoulder blade up, physically giving you the appearance of growing taller and longer. If you’re using your lats properly, it will feel like you’re physically elongating like a cat being pulled upwards. My coach used to joke that people who didn’t shrug tall their shoulders have ‘short stumpy arms’ and it somehow stuck in my head: grow tall, don’t be a tree stump. I like to think of shoulder elevation as “reaching for the cake”: keep reaching from your shoulder blades and sides continuously, as if you are trying to grab your cake.

To find shoulder elevation, first try to do cheating shoulder elevation. Intentionally try to tense your upper traps to bring your shoulders to your ears and find how much tension you can feel there when you try to breathe or talk. Then, go into a lunge and try to repeat this engagement and try to even add a bit of neck extension and a backbend. Notice how your body won’t feel stable to arch backwards, and your mid and lower back will immediately try to take over to help you bend. In addition, you may also feel that the front of your shoulders will pinch as you try to reach backwards, often causing a nerve tingle in your shoulders as well. If your fingers are losing sensation when you reach for something in a backbend, this is probably a sign that you are not engaging the muscles around your shoulder blades! (For more information, read this blog, “Why Do My Shoulders Tingle In Bridge?“)

Now, try to shrug your shoulders to your ears by relaxing through your upper traps and shrugging more from the lower part of your shoulder blades. Try to feel the feeling of wrapping and growing tall from your sides, where your lats insert and wrap behind your shoulder blades. Now, go into your lunge again and try to add the neck extension as you keep reaching for the cake on the other end of the room. Notice how you can pull your hips forward as your shoulders extend that you can also feel the sides and front of your body stretching. This is how to elevate your shoulder blades properly.

Play around with using this shoulder shrug engagement in your lunge with your chin to your chest, as well. You will notice that when the neck is not extended, it is easier to reach with your lats and shoulders. When you drop your head violently, the weight of your head can actually block your shoulder flexion (reaching overhead), making you feel you can’t reach as well. Often times, the shortening of your lats because of lack of shoulder engagement will also block your upper back from extending, dumping the bend lower down into your lumbar spine.

Secondly, shoulder protraction + external rotation can be thought of as “opening the gate”. If your shoulder blades aren’t separating enough when your arms are overhead, it will feel like your upper spine gets stuck and you can’t pull your upper back through your shoulders either. Shoulder protraction is *not* to be confused with closing your shoulders. Often times people will pull their shoulder blades apart by rounding their upper backs because shoulder protraction is most commonly taught as the top of your high plank. Yes, it will help with planks, but it will not help with contortion. Basically, you can keep your shoulders protracted with your upper back completely in extension. Proper shoulder protraction can happen when you’re in a deep upper back bend (such as a Mexican handstand) as well as when you’re in deep upper back flexion (such as in a L-sit).

To understand shoulder protraction with spinal extension, do a plank with your feet elevated on a chair. From here, arch from your lower back and extend one hip up and over as you’re looking in front of you and pushing tall from your shoulder blades. Keep your shoulder blades separating and use your neck to pull your upper back through your shoulders your your upper back is slightly extended. Try to keep the protraction as you lower down into your push up and back up. Notice how the shoulder blades separating is possible with an upper back bend and actually helps you to use your lats and chest muscles to push better!

Shoulder protraction comes from your serratus anterior, what I call the ‘armpit muscle’. The armpit muscle helps to pull your shoulder blades apart from the armpit, but it’s also one of the muscles that are least recruited in my hypermobile students. To separate your shoulder blades properly, you need to spiral in from the armpit, not close the entire shoulder. To find your serratus anterior in a backbend, go into a kitty stretch with your elbows on a yoga block. Intentionally push your fingers into each other (I call this “scheming fingers”) and think of pulling your elbows apart on the yoga block to separate your shoulder blades. Try to flex your spine first to feel your armpit and lats stretching then keep your engagement as you add the arch, trying to pull your neck to look at your thumbs. If, at any point, you lose the armpit engagement, you will instantly feel the stretch dumping into the front of your shoulders and the elbows will start to slide outwards: what we call “winging” the shoulder blades.

Take note that people also sometimes externally rotate to wrap their armpit in without their shoulder blades moving: this is also incorrect. You can pull in your armpit without elevation and protraction, and this usually results in a closed shoulder. The muscles in charge of external rotation (the infraspinatus and teres minor) aren’t the same as those in charge of protraction (serratus anterior). Hence, it is possible to externally rotate the shoulder without actually separating the shoulder blades (something I have seen many hypermobile students do). Always try to feel the feeling of your shoulder blades separating when you pull your armpit in, so you are not neglecting protraction just to prevent someone from seeing the inside of your armpit!

Shoulder shrugging and wrapping is vital to a lot of contortion shapes where the shoulders are in an open position, such as full cobra, teardrop, any kind of Mexican and your basic needle or ankle grab.

What is “Winging”? Why Is It Bad To “Wing” My Shoulders To Get Deeper?

When someone doesn’t have enough stability to pull their shoulder blades apart using their serratus anterior (your armpit muscle), they will inevitably want to turn out their shoulders to achieve this effect. This is what we call winging or shoulder internal rotation. How do you know if you’re winging? If you see the pit of your armpit facing outwards, you are probably doing it. Hide your armpit: make it face where you’re looking!

Have you ever tried to reach back for your feet in a backbend and realized that your elbows immediately splay out to the side, making catching your feet impossible? This is probably because you are not using your armpit muscle but you are relying only on your rotator cuffs to do the work. Likewise, people with flexible shoulders will often neglect using their serratus and turn out the shoulders because it will give you the false sense of getting deeper in a stretch. However, overhead shoulder flexion with no serratus engagement will cause your shoulder blades to retract (the gate to close inwards), blocking your neck and upper back from pulling through your shoulders. You are, effectively, blocking spinal extension if you choose to wing your shoulders in everything. Externally rotating the shoulder (wrapping inwards through the armpit with your rotator cuff muscles) helps fix this, yes, but the serratus also has to work with your rotator cuff to achieve the desired effect, especially when you bring this engagement to weight bearing positions. If you superficially externally rotate the shoulder joint to hide your armpit from view, you can still do so without pulling your shoulder blade apart actively; this limits your range-of-motion when you want to grab lower, such as grabbing your knees.

In addition to blocking spinal extension or making active grabbing of your limbs more difficult, winging will also cause pinching in the front of your shoulders if you do this in a weight-bearing position (such as bridge) or when you pull into a deeper bend (such as in full cobra). If you get used to this engagement, you run the risk of injuring your deltoids and rotator cuffs. Moreover, you wing your shoulders in a heavy position such as a Mexican handstand, you are basically asking for a shoulder dislocation!

However, this is not to say that winging is bad period! There is a proper way to turn out the elbows and shoulders properly, just as there is a proper way to turn out your hips. When we turn out our hips actively, we are using our side glutes and abductors. Likewise, when we turn out our shoulders, we have to use our serratus anterior and lats to do it actively. Proper turn out actually helps your shoulder blades to separate when your arms are overhead, helping you pull deeper into a bend. This can be seen in shapes such as box and face frame. Likewise, if you do full cobra grabbing the inside of your legs, you will be turning out the armpit a bit, but this is fine as long as you’re still engaging from your armpit muscle!

A lot of hypermobile people come into contortion with underdeveloped serratus muscles and excessive shoulder flexibility: this is basically a recipe for injury. Contortion isn’t just a matter of getting deep in a stretch, but using the proper muscle engagement to do it safely and sustainably. Yes, you may still be able to do full cobra with winged shoulders, but you will be crunching into your lower back and pinching your shoulders, which will cause issues in the long run. Bad habits are much harder to fix than building good ones, so try to start off with the right shoulder engagement, even if it makes shapes feel much harder initially. Your shoulders will thank you!

If you are someone who struggles with the proper “shrug and wrap”, I encourage you to revisit basic physio exercises to find which muscles you use to retract, protract, elevate and depress your shoulder blades. Use a mirror, consult a medical professional or coach to observe you. Develop the proper habits first, and the tricks that you so desire will come to you.

Contortion and Mexican Handstands: Shoulders Closed And Open With Shoulder Protraction

For contortion handstands, the shoulders are technically closed, but we are still elevating and protracting (shrugging and wrapping). If you over-engage your upper traps, however, you will feel your neck can’t extend to open your upper back. Slightly relaxed upper traps as you maintain your tall shoulders will enable your upper back to pull through your shoulder blades, allowing you to look ahead and breathe comfortably, as I do in the right picture. You should be able to talk and turn your head freely in a contortion handstand if you are engaging your shoulder blades separately from your upper back and neck.

In a straight handstand (with the shoulders open), you will be shrugging and wrapping, but make sure the action of elevation comes from your shoulder blades and not your upper traps. If you elevate only via your upper traps, your shoulders will still not feel supported and you may put strain on your rotator cuffs, also possibly making the front of your shoulders pinch. The amount of internal or external rotation at the end of your shrug is subjective and depends on the individual, but the most important thing is to feel stability in your shoulder joint as you’re pushing.

In a Mexican handstand, you basically are shrugging and wrapping while leaning into an open shoulder (shoulder flexion). This is similar to bridge engagement, only with extra shoulder flexion. You need to stay at the top of your shrug for the entirety of your shoulder flexion as your hips/ lower body counter-balances your handstand. The moment you collapse in your shoulders, your shoulder blades will want to collapse towards each other, causing your armpits to want to turn out and your shoulders to dislocate. As such, I always encourage students to shrug as tall as you would a one arm handstand before leaning into your shoulders in any position. A little external rotation through the rotator cuffs will also help prevent you from passively turning out your armpits. Bad shoulder engagement in a Mexican handstand or bridge will kind of look like the shoulder is closed and the chest is dropped even though the shoulders are behind the wrist. Thinking of lifting from the chest as you lean will also help you find a safer range of movement at the end of your shoulder flexion. It will also allow your butt to go over so you can counter-balance your lower and upper body properly.

Neck Engagement: How We Open The Front Body

Lastly, neck is the other key component which I have talked about briefly in previous parts of this article. As mentioned in some other blogs (such as “How Do I Engage My Core In Contortion?”), neck extension comes from both your deep neck stabilizers and your superficial neck muscles. Tucking in or out through your chin helps you to active your deeper neck stabilizers so you can use your superficial neck muscles to pull your neck into extension safely. This is what I call “turtle neck”: when you tuck and pull from the sides of your neck as if you were a turtle coming out of its shell. Be a happy turtle, not a scared turtle!

If you are able to use both your deep and shallow neck muscles to perform turtle neck, you will feel you can support the weight of your skull and you bend backwards. Letting go of your neck muscles when you bend backwards with your shoulders overhead usually makes your shoulders collapse too, thus making spinal extension feel impossible, as the neck is effectively blocking it by being a dead weight (what I call “watermelon head syndrome”). In addition, it also makes breathing next to impossible, as your turtle neck muscles are also in charge of helping you breath shallowly in deep positions. Without active neck extension, you run the risk of fainting from a simple lunge.

Proper neck engagement will allow you to pull your sternum through in various bends! I think of the neck as the leader of the front body. Pulling your neck through your shoulders in positions such as scorpion handstand allows you to breathe better, but also creates more space in your chest. It also help you to direct where you are bending. In a C-back stretch (right picture), for example, the neck is the main driver pulling your head towards your butt while your shoulders are overhead and pushing. It works best when the shoulders are already pushing properly, allowing your neck to pull your upper spine through easier!

In Summary…

Upper back extension is a combination of pulling from the front to open the chest (from the neck) and using the shoulder blades properly to open the upper back. A disengaged neck makes you sink into your shoulders and also obstructs your breathing. A disengaged shoulder girdle can cause tingling, rotator cuff impingement and other fun issues.

If there’s one thing you take away from this blog: shrug and wrap when your arms are overhead, and squeeze and “yawn” when your shoulders are by your side. Improper shrugging and wrapping will cause you injuries, so the sooner you build the habits the better! If you want to do more advanced postures such as Mexican handstands or even needle scale, you will not be able so safely if you do not shrug and wrap properly. I have so many students who come to me with years of bad habits, and it takes *a long time* to correct these habits so as to be able to execute skills safely. If you build good habits from the beginning, skills will come to you easier and safer, and you won’t have to spend months fixing something because your ego told you you can get a bit deeper if you cheat.

What is natural for your body isn’t usually the correct engagement, *especially* if you are hypermobile. Learn the right way to shrug and wrap and let go of your ego’s need to push deeper. The shapes will come, and you will be opening new dimensions of possibility in terms of what you can do, because you have created a solid foundation to work from!